Comments on Programme di Valorizzazione for Bussana Vecchia

Versione italiana

Borgo di Bussana, 1930 & 2013

Please sign the petition to save Bussana Vecchia.

Updated: May 14, 2018

This document provides comments to the development program (Programme di Valorizzazione - PdV, Italian, 32MB), dated 24/11/2017, written under responsibility of the Demanio. The Demanio is the Italian State Property Department which, after 130 years of neglect, suddenly decided it is the owner of the town and considers the residents illegal.

What will happen to Bussana Vecchia if this "enhancement" program will be executed?

1) Inhabitants will be evicted and their houses, which have been painfully recreated over dozens of years in a spontaneous effort, will be sold to other interested parties (scavengers). Groups of the houses will be sold to the highest bidder to create a hotel. The present artist inhabitants have received ridiculous fines (some higher than € 100,000) for ten years of "illegal" occupation of a series of ruines that was ignored and deliberately destroyed by the authorities in the past 130 years. Even if only some of the uninhabited houses are sold it is unclear what the new owners will have to do: the town will be completely inaccessible for many years, plans and guidelines for proper reconstruction in historic style do not exist. Tourism will disappear so shops cannot exist, and restaurants and bars will be closed.

2) In the next step, all infrastructure will be eliminated (streets, sewers, water lines, electricity) in order to place new systems.

It is unclear how this can be done when the present structure of the town has not been studied and nobody in either the Demanio or municipality of Sanremo has a clue about its final structure. Given the six tiny streets in town this means the town will be inaccessible for years. Since there is no idea in the PdV about what the town will look like it also is unclear how the new utilities will need to be constructed. Afterwards, supposedly, the "original" cobblestone pavement (constructed by the artist-builders after its destruction by the authorities) will be reinstalled without considering the fact that the next phase will require heavy tools to be transported over these pedestrian streets thereby demolishing the new construction. The town will become an unhealthy, noisy, dirty, and dusty construction site for many years.

3) In the third phase, restoration works will start on the main (St. Egidio) church, the small Oratorio church, the hospital, and construction of a hotel (?) will start. Given the fact that Bussana Vecchia consists entirely of small pedestrian streets a new access road will need to be build. Costs for this access road, as well as improvements to the main (dead-end) road into the town have not been included in the financials. Additional power needs to be provided by diesel-electric generators. These will need regular refilling and probably will work 24 hours a day,. Tons of building materials, pipes, concrete and cranes to transport them will be needed.

4) Once these first three phases have been completed, which easily could take ten to twenty years longer than targeted, the Castello will be restored. It is unclear why the PdV, which considers this the most important historic building, plans it to be restored at the very end of the program.

While this restoration is in progress, almost as an afterthought, the PdV suggests that a plan for the promotion of tourism into the village will need to be written.

For the eviction of the inhabitants and execution of this completely unclear program, the government/municipality needs € 43 million, preferably from the European Union.

In this "dreamed" PdV, the government conveniently has forgotten several tens of millions euros to create access roads, stabilize the area, and do any maintenance. A business case to recover any of the (European) taxpayers money is not done. It probably was left out for a good reason, because the recovery of these investments will never ever happen, so a negative return on investment.

Again, please sign the petition to save Bussana Vecchia.

I will first provide a summary of the comments, followed by detailed comments.

Summary

- The Development program describes the historic and present state of the Borgo di Bussana / Bussana Vecchia and a plan of action for funding and the implementation of improvements. It fails to describe the historic events between the earthquake in 1887 and the start of the artist community in the 1960’s. A considerable part of town was purposely destroyed in the 1950’s by the authorities to evict (immigrant) workers. Where the older sections (Rocche and Montà) clearly have suffered from the earthquake, the Fascette area suffered from the destruction by the authorities. A substantial number of houses had greater damage from the explosives than from the earthquake, giving doubts about the validity of any ownership claims by the state or the municipality.

- The Development program fails to describe the spontaneous architecture created by the artist-builders which is unique in the world, applauded by architects, and a major reason for tourism.

- The Development program fails to describe the various ongoing legal procedures and naively assumes new planning and construction phases to start in 2018, without recognizing the many years that these legal procedures may still take.

- The Development program fails to describe the limitations and risks by erosion on the reconstruction plans of the town.

- It fails to specify the additional infrastructure activities, and their huge expenses, that have to be completed before any significant reconstruction of the town may take place.

- It provides a sketch of an “ideal” town, without mentioning the ongoing deterioration of the surroundings with its state prison, ghostly empty flower auction buildings, waste processing plants, and many disintegrated greenhouses negatively impacting tourism.

- It provides sketches of the historic buildings and their position on the map only based on a series of short visits from Demanio employees. Their information fails to capture the complex, interwoven, structure of the houses as result of the earthquake and explosives damage, thereby rendering floor space, and thereby “occupation” information, useless. It also fails to indicate the high-humidity conditions to which ground floor galleries and shops are exposed which limits their use.

- It uses demographic information that is incomplete due to the freedom of living offered by the European laws.

- It provides an estimation of expenses without including key expenses to allow access for reconstruction and tourism, thereby greatly underestimating the total cost for the program with multiple tens of millions euro.

- It completely forgets the high amount of annual maintenance expenses. Even those maintenance expenses are too high to be compensated by tourist revenue.

- It gives an estimate of a phased approach which, for unclear reasons, starts with the least important (evicting the inhabitants and selling concessions to buildings), followed by the construction of utilities, restoration of houses and creation of a hotel. The restoration of the actual treasures in town that are critical for tourism, the ancient castle and churches, is planned at a later point in time, without giving any indication how such buildings can be restored without first financing and creating major construction access roads.

- The creation of a strategy for the increase of tourism, which supposedly should generate the revenues for the hotel, galleries, and shops, is only foreseen to start in 2022. This reverse, illogical, approach without an attempt to create a business plan is useless to generate any of the desired funding amounts.

Overall, the Development program can, at best, be seen as a first exercise, incomplete and without value. A detailed follow-up study is essential to create an effective basis for requesting budgets for the improvement of Bussana Vecchia. Such study should place preservation of the spontaneous architecture by the artist-builders and its importance for tourism and its associated revenues at the center. It should include a proper business case and cost/benefit analysis. Such program cannot be created without the cooperation of the inhabitants and should aim at a solution which recognizes the many years of effort and money they have spent to turn this forgotten town into the treasure it currently is.

Chapter I

This chapter describes applicable laws. General observation is that this Development program refers to Legislative Decree 28 May 2010 No. 85 but fails to provide, in accordance with article 1212, the strategic and detailed financial aspects needed to designate budgets and approvals.

Chapter II

This historic overview provides details on the construction activities in town from medieval times up to the earthquake of 1887.

Key omission in this section (Chapter II.12 and 13) is the (convenient) absence of historic information of the period from the earthquake in 1887 to the start of the artist community in the early 1960’s.

The Borgo di Bussana was built in the medieval era to protect the inhabitants from pirate attacks. These attacks continued up to the end of the 18th century. Located on a hilltop, with only one small access road and with a semicircular placement of buildings around the castle, the Borgo was ideally protected. The access limitations also restricted restoration efforts after the 1887 earthquake: all removal of rubble and transport of building materials had to be done by hand by the inhabitants and is still done today.

The Borgo di Bussana is similar in structure to the nearby town of Bajardo. Bajardo suffered even larger damage from the 1887 earthquake than Bussana. The mortality at Bajardo was 300. At Diano-Marina: 250. At Castellaro, 40 people died and 64 seriously injured. Only two houses were still upright and the church suffered identical damage as the one in Bussana. In Bussana, 53 people died and 36 were injured. Nevertheless, all these nearby towns have been reconstructed while the Borgo di Bussana was abandoned by the state.

Bussana (L'Illustrazione Italiana, marzo 1887)

Images dating immediately after the earthquake show massive damage to houses. What they do not show is that a significant part of Bussana already was in rubble after the earthquakes in 1818, 1819 and the forceful earthquakes on May 26, 27 and 28, 1831: the Antologia Giornale di Scienze Vol XLII writes that twenty-four houses collapsed and another forty-nine houses (in the Rocche and Montà area) were in very bad shape. Together they form about one-third of the houses in Bussana. The town's two towers sustained significant damage in these earthquakes. During the earthquake of 1854 the watchtower, built in 1565 to defend the castle against Saracen attacks, collapsed onto several houses thereby further damaging this area. Many inhabitants from the Rocche and Montà area moved out towards the Fascette area and to nearby towns.

The Fascette area (the area south of the church, visible in image above) had minor damage. The walls and roof of the Oratorio and the aquaduct arches were intact.

Don Lombardi, who took the initiative to construct Bussana Nuova after the government failed to take action, reports in his 1887 diary that the inhabitants of the Fascette area could flee these houses via their regular entrances.

The Development program omits to describe that a few hours after the earthquake the municipality of Sanremo ordered that all inhabitants had to leave Bussana. The military police was brought in to make sure everyone was evicted. Orders were given to shoot at anyone who wanted to re-enter the town. At the time, there were still people alive under the rubble of collapsed houses. Some of them were found only weeks later, having died from frostbite and starvation, without wounds from the earthquake.

Several inhabitants risked their lives to circumvent the military police and entered town where they saved a young woman and two children, a boy and a girl, from under the rubble. While the inhabitants were forced at gunpoint to evict their town, the soldiers did not intervene when thiefs robbed the houses of all valuable posessions.

After months of delay, wooden shacks of poor quality were erected to house the evicted inhabitants. For this "aid" the devastated and forcefully evicted inhabitants had to pay a monthly rent.

After living for almost six years on the field outside their hometown, they had to move to the modern “new town” Bussana Nuova. They were forced to loan money to pay for their new land and houses. When they indicated they preferred to stay in their houses in the old town, the authorities cut the water supply to town and purposely demolished many houses that initially were considered repairable. Details about these tragic events can be found in Nilo Calvini’s excellent and honest book “Bussana, dall’ antico al nuovo paese”, (1987) which was underwritten and sponsored by the mayor of Sanremo at the time (details about Calvini's historic research can be found via above link).

In World War II, the town was occupied by the Nazi’s who placed two anti-ship artillery batteries with several cannons on the Bussana hillside, just below and above the old town. The nazi’s made old Bussana into their temporary home, not allowing anyone to near it. When they left, they cleared their magazines by firing into the deserted village. Historic analysis of these events is still in its infancy. Evidence of this occupation is, for example, provided by a (dated) swastika inscription in one of the houses.

After the war, the town was occupied by workers from the South (e.g. Calabria) and immigrants who tried to find work in the flower industry. To evict these inhabitants, the remaining houses were demolished (between 1950 and 1954) by the authorities using military explosives and demolition instruments. In addition to testimonial by the local population, the effect of the explosions is confirmed by the characteristic shockwave holes in the floors and ceilings of many houses in the Fascette area. Key example of such destruction is the building of the Osteria degli Artisti. Images show it still existed in the late 1920’s and so did many of the walls and arches of nearby houses. Altogether, close to one hundred fifty houses (about two-thirds of the total) have suffered from destructions by the authorities.

Osteria degli Artisti in 1920 and 1930 (complete with windows), and in 1954 (destroyed with dynamite)

After over eighty years of abandonment, the emerging artist community invested labor and money to reconstruct the town. Initially by manual removal of the debris caused by the municipal destruction from the 1950’s in the Fascette buildings near the entrance of town and by restoring minor earthquake damage. After the basic restructuring of these buildings, the artist community concentrated on removal of earthquake debris and reconstruction of houses closer to the church. This collective process has been painfully slow and has taken dozens of years.

Scholars have recognized this spontaneous building activity as exceptional in the world: reconstruction was done in a wholly anomalous situation, without regulatory bounderies, in an administrative vacuum created by the refusal of authorities to take any action. The spontaneous reconstruction shows the unique interaction between the individuality of each artist/builder and its construction efforts, translating housing needs directly and freely into the most appropriate design and to exploit the structural medieval feature of the buildings.

Architects and university researchers, Italian and international, applaud the fact that, despite the absence of building regulations, the reconstructed Bussana Vecchia became more original than nearby rehabilitated towns where regulations resulted in an unrealistic uniformity.

This is a key reason why Bussana Vecchia is so interesting for visitors. Rather than trying to (again) destroy this unique situation by restructuring the town as planned by the Development program, the municipality/state should focus their efforts to maintain and preserve this treasure of spontaneous architecture. Traditional reconstruction efforts (at significant expense, likely to equal if not exceed the amounts mentioned by the PdV) could better be aimed to restore the historically important Rocche and Montà areas, which the state had abandoned since they were damaged in 1831.

With all the evidence about their abandonement and deliberate destruction of the Fascette area by the authorities in the past one hundred and thirty years, its recent plans to restore this 'historically important area' is totally incomprehensible.

Based on the lack of access into this town with only pedestrian roads there is no indication that any new reconstruction, either government or privately sponsored, can be done any faster or at significantly lower costs. More on this topic further down in this document.

Chapter III

This section identifies areas surrounding the Borgo di Bussana. It lacks details about the use of the area, the geographical situation and risks.

The promontory position of the town on a hilltop limits access to one narrow road with several hairpin curves. Road maintenance has been kept at, or below, minimal level. The road is unfit for heavy and/or wide construction vehicles. Road deformations are only repaired provisionally. After a landslide in 2015, repair of this access road took several months, leaving the town inaccessible. Repair of the road was only initiated because the cemetery of Bussana Nuova could no longer be accessed. Nearby roads have not been maintained at all. Major investment in this access road construction is needed before any significant restoration efforts in the town can be initiated. Costs will be multiple million euros and construction time will be several years. These have not been included in the Development document.

The chapter fails to indicate that Liguria’s major railway artery was constructed directly underneath the Borgo di Bussana. Every few minutes, the vibration of passing trains is felt in town as miniature earthquakes. Creating new or alternative access roads need to be done with caution to avoid affecting this railroad artery.

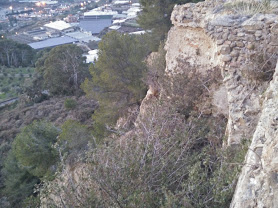

For the analysis of the touristic value it is essential to provide greater detail about the geological aspects. The hilltop on which Bussana Vecchia resides primarily consists of soft stone. As can be seen from the Valle Armea as well as along Bussana’s access road, major sections of the “calanchi” (badlands) rock near the perimeter of town are unstable and several houses near this area have collapsed as result from erosion.

Collapsed house because of hillside erosion (access road)

Geological erosion will continue to damage and reduce the area surrounding the Borgo di Bussana, not only on the West and South side as mentioned in the document, but on all other sides. Minor landslides occur everywhere around town during periods of heavy rain. With exception of landslides affecting the access road, repairs are performed by the inhabitants and volunteers that maintain the footpaths, not by the municipality.

Great efforts and investments are required to make sure the erosion does not cause further damage. Estimated costs will be multiple million euros. This aspect is mentioned in Section V of the Development document without providing an estimate of the (essential) costs to safeguard the risk areas.

In addition to the nearby historic sites mentioned in the Development document, it omits the fact that the North and West part of town offer a view of State prison buildings in valle Armea. The view towards the coastline on the South is destroyed by the massive flower auction buildings that have been unused for over twenty years. The majority of greenhouses that are visible from town are in state of severe neglect and collapse. These items all negatively affect (growth of) tourism.

Surroundings: deserted flower auction buildings, abandoned greenhouses, state prison

Chapter IV

This section with analysis of buildings is incomplete. It does not reflect the actual housing situation. Its two-dimensional approach excludes the many building levels, from galleries and storage rooms at street level, to higher level floors. The destruction by the earthquake (and later destruction efforts by the authorities) resulted in buildups of rubble causing multiple floor levels being interwoven.

Few houses have been preserved in one piece and only part of the rooms could be restored into a usable state. The majority of present living areas thus consist of interconnected rooms from several original individual houses, thereby creating a unique spontaneous architecture. Stairways between floor levels and passageways between rooms that were full of debris from the earthquake and/or later destructions often could not be excavated and were circumvented by using accessible passages from nearby houses.

None of this has been reflected in the plans presented in the development document. The overview lacks the detail allowing for a proper reconstruction of houses. Ancient cisterns and the water collection tubes to fill them have been overlooked. Passages and stairways from the ground floor shops, storage rooms and stables to the upper floors of the houses have not been taken into account. The subterranean ducts and caves leading to and from the castle have not been investigated. The medieval walls, streets, and location and size of the old cemetary have been incorrectly drawn in the plans. These elements need to be studied in great detail before any restauration of (parts of) this ancient village is possible.

The reference numbers stated in this section are often incorrect and deviate considerably from the geometra-created precise indications in earlier (e.g. 1981/1983) Catasto files. The inaccurate plans in this chapter are insufficient to be used as basis for occupation purposes.

Three main historical areas in the Borgo di Bussana are described in this section of the PdV as follows:

“Le Rocche” (the rock) is the oldest area. It is comprised of the Castello and surrounding buildings, protected by a fortified wall in the 15th century. This is the area most damaged by the earthquakes and has seen little reconstruction, neither by the state nor by the artist community. Press reports from 1831 state that twenty-four houses in this area already had collapsed in the major earthquake on May 28 that year. Their inhabitants left. There was no government support to rebuild these houses. This is the historic area that would benefit most from government, EU, and/or private sponsorships.

“La Montà” (the mountain) is the first strip of buildings around the Rocche area and describes the area North of the St. Egidio church, the Watchtower, and nearby houses. The area had its own fortified wall (built in the 16th century) for protection against pirate attacks. These buildings have seen few changes since the 1887 earthquake due their access limitations. According to newspaper reports, forty-nine houses were badly damaged in the 1831 earthquake and collapsed in the 1887 earthquake. Restorations in this area were only initiated when the access via the Fascette area became feasible. Restauration efforts were more complex and restrictive due to access problems, since all materials needed to be carried by hand. This area would also benefit greatly from government, EU, and/or private sponsorships . Some of the buildings belong to the Church. Most recent municipality-initiated restorations of the St. Egidio church have taken significant labor and expenses. They also took several years. Even after completion of the basic repairs (2002, 2003, and 2007) the church was not considered safe for the general public and has been closed ever since. Further restoration effort will take many more years. This contradicts the implementation plans and financials sketched in Chapter VI.6.

“Le Fascette” describes the newer parts of town, near the village entrance. Omitted in the Development document is that, apart from minor damage of wooden roofs and top floors by the 1887 earthquake, the major damage to houses in this area was done by the authorities in the years after the eartquake to force their inhabitants to the new town, and by means of explosives in the 1950's (euphemistically described in the document as “building interventions”) to evict immigrant workers. The deliberate destruction of all first and upper floors was done to make this 'historic' village completely inhabitable. The Osteria (see above images) and many other buildings in the Fascette area were completely destroyed. Unlike the earthquake, which affected the thick walls of the houses in the older parts of town, the Fascette houses show typical explosives (pressure) damage in floors and ceilings.

Typical examples of (repaired) damage in ceiling caused by explosives

Based on their short visits (often less than ten minutes per house) by Demanio staff that had no formal background in historical architecture and construction, the Development document concludes that there are no buildings in “good” or “optimal” condition. This statement is subjective and not based on building standards. Within the Borgo di Bussana there are multiple buildings that have been restored taking seismic and other risks into account, with significant higher quality of construction than houses in nearby towns that comply with building laws. Example is the nearby medieval town of Bajardo, which suffered worse from the 1887 earthquake. It has been restored using construction practices and materials that are considered inappropriate by this development document but nevertheless is not seen as a risk.

A proper evaluation can only be done based on detailed analysis by experts. This is confirmed by the authors of the development document. The time required for such proper analysis will take multiple times the brief analysis done during the year and: likely several years.

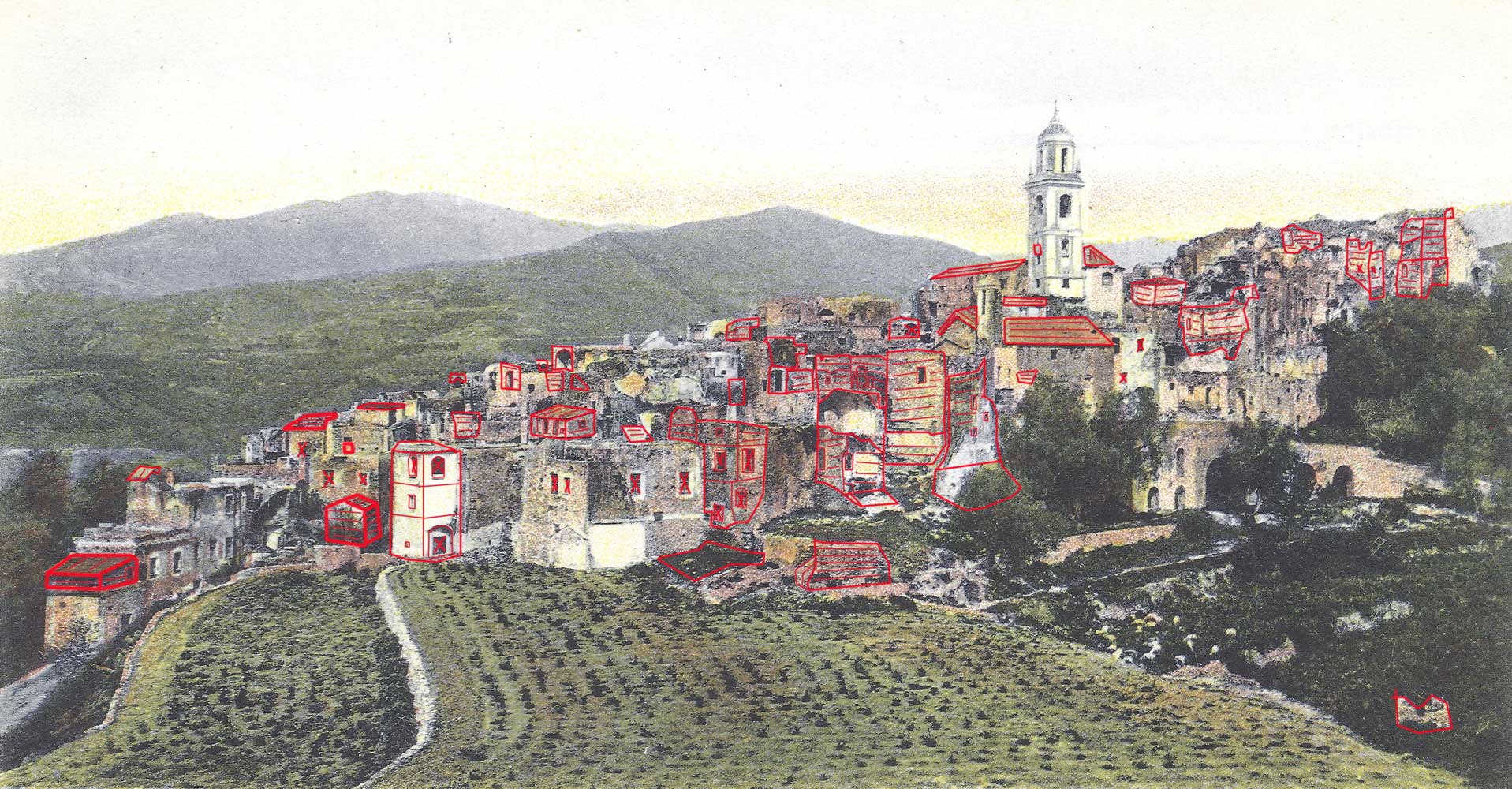

Photo comparison 1887 - 1954: houses destroyed by authorities after the earthquake

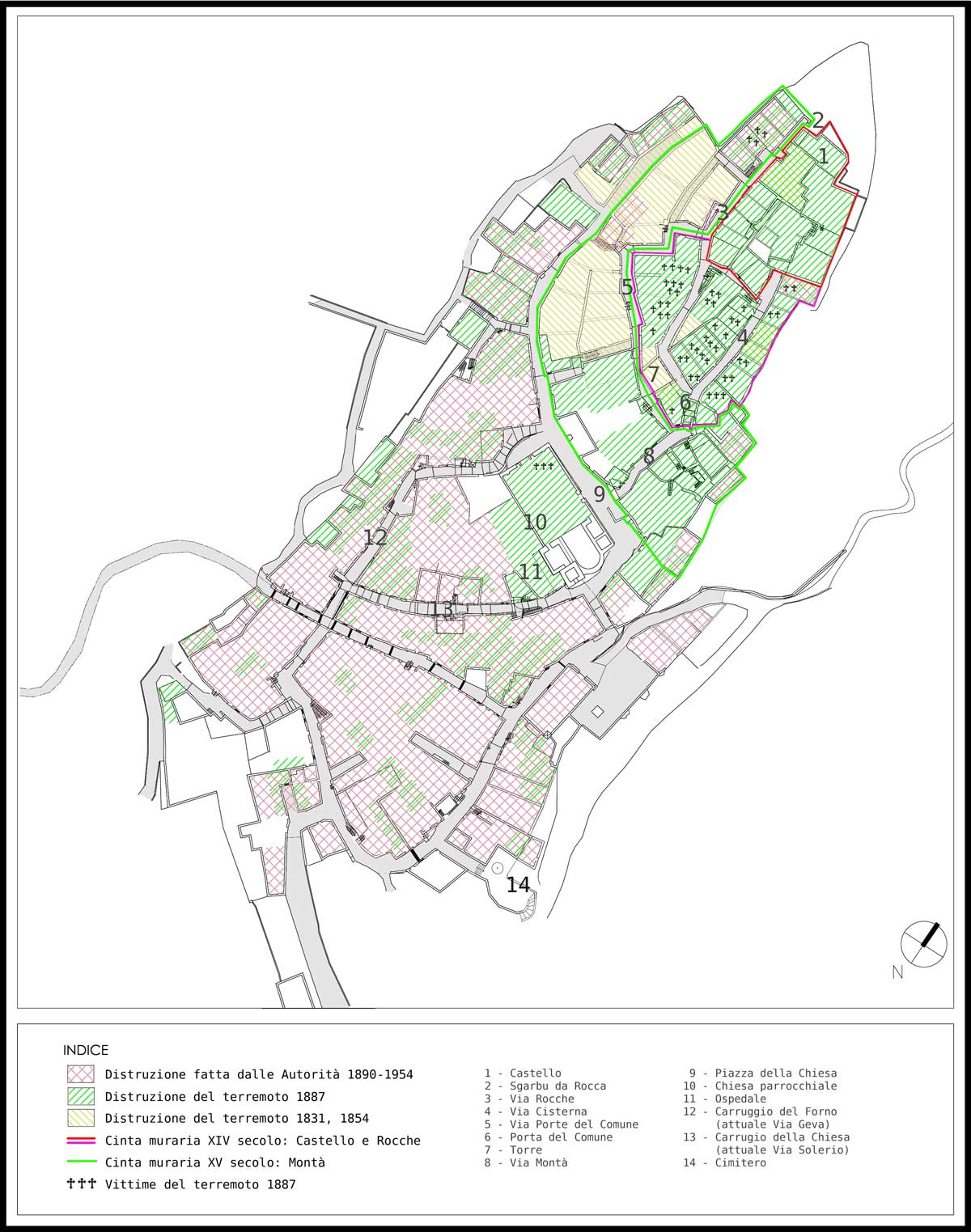

I have recreated the street plan of old Bussana using multiple drawings and images of the town dating from 1772 up to 1954. This information was augmented with the help of aerial and satellite images as well as altitude information. Last but not least, it was updated with information from historic analysis and personal input from present and former inhabitants.

The image below shows Bussana as it probably looked like prior to the 1831 earthquake. An outline is given (yellow hatch pattern) of the (24) destroyed houses in the Rocche and Montà area by the 1831 and 1854 earthquakes. In green hatch pattern, an indication is given of the damage done by the 1887 earthquake. This damage includes both collapsed houses in the Rocche and Montà area, the St. Egidio parochial church, as well as lesser damage in other parts of town (primarily top floors and wooden roofs).

The lower, Fascette, area of town had much better earthquake resistance due to the buttresses between the houses. Via Donetti (now via degli Archi), via Ospedale (formerly via della Chiesa), and via Geva (formerly via del Forno) have well over a dozen of these buttresses.

All victims of the 1887 earthquake were in the upper area and in the church, as indicated on the map below.

Damages done by the autorities (Sanremo municipality, corps of civil engineers, and army) are indicated in red cross-hatch pattern. A few dangerous houses were taken down immediately after the earthquake. Many (at least 56) houses in the Fascette area were considered habitable, but were (partially) destroyed between 1890 and 1892 to make sure its owners/inhabitants would have no other choice than to accept the government plan to move them to new property (at their own expense) in the New Town (Bussana Nuova). Another action to force the inhabitants out was the destruction of the aquaduct water connection into town in 1892.

A second massive round of destruction by the authorities was done in the 1950's to evict immigrant workers. The majority of the upper floors and stairs

were destroyed with dynamite. Some houses, such as the building presently known as the Osteria degli Artisti and adjacent houses, have been completely demolished. Also the Oratorio church was destroyed in this action.

Map of Bussana showing streetplan and destruction by earthquakes and authorities between 1831 and 1954

Historic evidence from multiple sources makes it clear that the vast majority of houses in the lower section of town were not destroyed by the earthquake(s), but by the authorities. This puts the plans to restore this area, which the Development program considers of 'historic importance', in a very strange light.

Panoramic image of a house destructed by the authorities

Why would the European Union, or any other source of funding, grant many millions to restore the damage that was inflicted on purpose by the Italian authorities?

Only for the Rocche and Montà area this would make sense.

Chapter IV.7:

The demographic analysis in this section has been based on government records. It shows only part of the actual population. European law allows citizens to live anywhere in the European Union without the need for a residence permit. The Italian government specifically indicates this right (since 2007) to avoid unnecessary administrative efforts and to limit possible financial and legal responsibilities related to insurance, social welfare and other benefits. The actual population of town is substantially higher than mentioned in the document.

Besides age and national background, the demographics section fails to indicate that the vast majority of inhabitants live below the minimum income level. None of them are able to generate any significant income from their damp shops and galleries, which are open only during the short periods in the year when tourists flock the town.

This chapter claims an area of the Borgo di Bussana to be property of the Demanio. It fails to indicate that ownership of a significant number of houses and/or non-applicability of Demanio claims confirmed by various legal procedures including highest Cassazione court rulings.

Chapter V: Territorial constraints

This section describes the area around the Borgo di Bussana as predominantly agricultural (Chapter V.3), without mentioning that the majority of fields and greenhouses have been unused and in neglected condition for many years as result of the fast decline of the local flower industry.

Chapters V.3 and V.5 indicate several areas around the Borgo di Bussana as geomorphical and hydrogeological “highly instable” (see also comments to Chapter III) without providing indications of the efforts that need to be done to eliminate or, at minimum, stabilize these risks. Costs of several million euros and several years of effort will be needed before these areas are sufficiently safe to support reconstruction work on the Borgo di Bussana.

Chapter V.7 conveniently points to the few surrounding areas that have limitations industry and noise as well as pollution. It omits the other, dilapidated, areas surrounding Bussana that house noisy construction and demolition companies, landfill and other waste management areas giving air and water pollution risks (such as the toxic fumes emerging from the large fire in a waste processing factory in area APA-11 in autumn 2017).

Fumes emerging from waste processing plant in Valle Armea (2017)

Also, the large area that contains the millions of square meters of flower process and auction buildings that have been empty for many years (APA-13) have been omitted. For a proper analysis all areas around Borgo di Bussana need to be taken into account.

Chapter VI: Valuation of property

The development exercise action correctly states that it is only the first of a series of actions towards the reconstruction of the Borgo di Bussana. Key priority is to make the town safe, accessible and usable and install communal facilities. Current water, sewer, and lighting in the streets and houses have all been paid for, installed, and are maintained by the artist community, without any state involvement or expense. This effort has been going on for several tens of years and a compensation for these efforts would be fair.

For unclear reasons, second priority is given to the restoration of buildings with greater architectural value; according to the development document these are in the ancient parts of town in the Rocche and Montà sections and comprise the Castello, the Egidio church, the Oratorio, the hospital and ancient cisterns.

This section of the development program provides draft plans and financials for potential future reconstruction that are naïve and unrealistic.

Center for earthquake survey (Ch. VI.2.1)

Although interesting from a scientific perspective, this initiative has negative touristic value. It may be hard to explain to tourists why the state has abandoned this historic town for over 130 years and, infact, deliberately destroyed about two-thirds of the town to make it useless for new inhabitants. Moreover, it will be difficult to explain why the State has made so little progress even with towns that recently suffered from earthquakes (e.g. L’Aquila, Amatrice). The document specifies the interest to demonstrate to the audience the impact of earthquakes on walls and houses. It forgets to mention that the houses in the Borgo di Bussana have been built with a methodology dating back to the Roman era: while these houses were constructed by local masons using sand, lime and rubble stone from nearby river beddings, buildings elsewhere in Europe were constructed using bricks and mortar. In the century that Bussana was built, Gothic and Renaissance style architecture was the standard. Having a center for the study of earthquakes in a town with construction practice that does not match the majority of Italian cities does not make sense.

Ecological center (Ch. VI.2.2)

After 130 years of neglect by the authorities, the infrastructure in the Borgo di Bussana has entirely been constructed by the artist community in a spontaneous effort. The town’s sewer as well as the water distribution system was done by private construction. The majority of houses share access to drinking water due to supply limitations. They rely on water tanks to secure sufficient water when access to the main water system fails. There is no access to the gas network for heating in the cold season. The electricity network constructed by ENEL is erratic and insufficient to provide electricity for the basic needs of the majority of households. Any of these networks is insufficient to provide utilities to either the Egidio church, the Oratorio, certainly not to the Castello and surely not to a hotel with modern amenities. Public street lighting is absent. The only lighting is provided and paid for by the inhabitants.

Moving from this 1950’s status into a modern ecological center will require massive construction work, time and money. With exception of street lights this effort has been omitted from this development document. Reconstruction of this aspect will require excavation of all streets and new connections from the nearby valley to the Borgo di Bussana. In itself, this activity needs to be completed before any other restoration activity may start. It will take several years, during which the town will be completely inaccessible for tourists, and will cost between 5 to 10 million. This amount is not included in the development document.

The Fondo Ambiente Italiano (FAI) has offered to support the reconstruction of the Borgo di Bussana and establish both an earthquake research and ecological center. Public voting placed Bussana to the third place of the FAI list. Support by FAI would be a very logical solution for the Borgo di Bussana. For unclear reasons there has not yet been a follow up by FAI.

Community section (Ch. VI.2.3)

This chapter briefly sketches an essential element: after the incomplete analysis by Demanio officials, a detailed survey of the buildings is required before any constructural (re)design can be done. This effort will take at least several days per house, performed by experts in this pre-medieval construction practice. It will take multiple months to analyze and evaluate the architectural specific of the larger buildings (e.g. the Castello) and create a restoration plan for each of them.

Costs and time for this effort have not been included in the development document. Based on my reconstruction analysis and (3D) architectural designs of one house it will take three to five years and € 2 million in cost to do this effort. Key limitation is the scarcity of experts in medieval building architecture. Few of such experts exist in Italy and they already have many years backlog in the edevelopment of thousands of key historic sites (such as L’Aquila) which have significantly higher intrinsic and social value than the restoration of an “artist community” tourist attraction in Liguria.

Chapter VI.3: Planned activities

Fase I:

For unclear reasons, the list of planned actions in the development document starts with activities that relate to the inhabitants and their houses, such as issuing real estate concessions via lottery to interested parties. This is the opposite of the conclusion in the document placing key focus on the stabilization of the area, access roads, and safety. How can concessions be given for real estate when a detailed survey has not been completed and guidelines for proper historic reconstruction under strict safety regulations have not been established?

The document suggests that any inhabitants that have paid the penalties recently issued by the Demanio for so-called illegal occupation may be invited to participate. The document does not mention that these penalties represent a highly unrealistic value that is far higher than the present price for real estate in the area. A methodology or calculation approach for establishing the penalties is absent and they have been based on a brief and highly inaccurate survey. They appear to have been established primarily to create a basis for eviction of artist/inhabitants (families with children and many retired persons) rather than a constructive approach to support the reconstruction of the town.

With this action plan the development document clearly shows its true nature: eviction of the inhabitants is seen as key, rather than preserving and restoring a medieval town of key historic value which was only decided after 130 years of abuse, deliberate destruction, and neglect and only emerged as result of the spontaneous and architecturally praised building efforts of these same artist community inhabitants.

Multiple legal procedures (not mentioned in the development document) have been ongoing for over twenty-five years and, with the expected frequent involvement of the court of Cassazione and slow legal progress in Italy, may easily last another twenty-five years. The ambiguous situation of the inhabited property in the Borgo di Bussana (which the development document considers of lesser historic value) can only be resolved by cooperation between municipality and inhabitants.

Given their touristic value it would be logical to focus subsequent restoration efforts on the key monumental buildings and the historic center (which is largely uninhabited).

Fase II:

The document describes urban infrastructure activities to bring utilities into town. It does not mention that, prior to this phase, overall access to town in the form of improved roads and stabilization of the eroded rock areas will need to be completed. Planning and realizing this activity alone will take several years and 5 to 10 million euros and, from planning to completion, five or more years.

Without this effort, the public works as planned in phase II cannot start.

It does not offer a solution what the concession holders, which the document expects to select in the first phase, need to do in the interim and how they may recover their expenses. In absence of public works and utilities, reconstruction of houses may actually only start after completion of phase II. The cost of phase II in itself will require another 5 to 10 million euros and, even with a tiled approach, will take three to five years from planning to completion.

A recent article in Italian newspaper La Stampa Economia (Dec. 31, 2017) places Italy in 108th place (behind Gambia) in the ability to execute projects. Other Western European countries use 200 to 400 days to complete an “average” project. In Italy this is 1120 days. In this light it is hard to believe any significant reconstruction work in the Borgo di Bussana can be completed prior to 2030. The main work on access roads, stabilization of the area, and public utilities in the town requiring underground work in the narrow pedestrian streets will block tourism for a period of up to ten years, thereby eliminating any positive effect on tourism in Liguria or the ability of concession holders (if any) to generate any income. The experience from other projects (via Aurelia bis, Molise earthquake) is not positive.

Project execution example: 10 year delay of nearby via Aurelia bis due to 'design interventions'

The planned first phases in the development document are a guarantee for economical failure and disruption of any tourism that presently exist in the Borgo di Bussana. The international nature of the artist community in town will make this failure highly visible in both the Italian and international press.

Fase III

It is only in this phase that restoration works of the Borgo di Bussana are initiated. From above information it is clear that this will likely be after 2025, or later, and only if current legal procedures and new procedures as result of the recent assigned penalties by the Demanio have been completed. This is extremely unlikely.

In this phase suddenly the construction of a “hotel” the addition of “bars”, “meeting places”, and “recreational facilities” in the ancient Montà area is foreseen. Apparently the development document considers these all to be a useful modification in a historic medieval town. The feasibility to integrate typical modern hotel facilities such as full bathrooms and elevators within the architecture remains unclear. This “Disneyfication” phase appears to be a total deviation from the initial goal to restore the medieval town. The only positive comment to this phase is the statement “This program considers that the existing residential destination can be maintained in order to make the village inhabited and enjoyed at all hours of the day.”

Bussana Vecchia: construction site 2019 – 2039?

This Borgo di Bussana fairy tale does not take into account the tourist access limitation of this dead-end hilltop town. The Borgo di Bussana enjoys a large influx of tourists only in late December and from mid-July to September. These are the only weeks when the parking area is filled and several hundred tourists visit the town every day.

Tourism is highly dependent on weather: during the week before New Year, tourism is stimulated by warm weather conditions. Influx on tourism during rainy days is minimal.

Adversely, the influx of tourism during the high-season summer period is determined by overcast days. On sunny days, of which there are over 300 in this region, tourists enjoy the many beaches and may only visit the town for some evening drinks. Only on the overcast summer days, tourists opt to go sightseeing and the Borgo di Bussana is only one of a series of choices of historic towns in the area. The decisive factor to select the Borgo di Bussana is its “hippie” artist community history with its spontaneous construction history. Without this feature, the influx of tourists may quickly disappear. Preservation of the artist image and structure of the village is as important as the preservation of the historic buildings in the Montà and Rocche areas.

During the other 40+ weeks in the year, tourism in minimal and insufficient to create any significant income for the art galleries, the bar and restaurants, nor for the B&B places. Visitors often are hikers or bikers or come to have a light meal at the bar or restaurant. Foreigners (many from France) visit the town during the few weeks of autumn and spring vacations. Their quantities are small compared to the influx from Italian tourists from the Milan and Turin areas during high-season. Revenue from tourism may support only a handful of businesses in town, primarily food and drink places. The most significant income is generated by the bar and restaurant that both are outside the claimed property area of the Demanio. Only the bar is open all year. All restaurants close during winter. Even at high season they may not be open all day due to lack of customers. There are three restaurants of which two are more closed than open. Income from tourism is insufficient to cover expenses.

It is unrealistic to expect that a major investment will change this behavior. Even with improved infrastructure and public utilities, tourism is presently below 50,000 per annum with little ability to grow. Tourism capital spending (range of €5 - €10 per person, primarily on consumptions) results in a total spending estimate of less than € 500,000 per annum: insufficient to support even the few dozen galleries and shops.

Last but not least, the development document fails to notice that all ground floor galleries and shops suffer from an extremely high humidity of more than 80%, even during the touristic summer season. As any of the inhabitants may testify, multiple (professional) activities have been undertaken at great expense to reduce this, without significant effect.

The moisture and mold buildup during the colder months need to be cleaned and repainted every year. Art works cannot be stored in the galleries during winter. Dehumidification machines are needed to reduce the humidity to a point where the shop keepers are (barely) comfortable.

The humidity is caused both by the direct placement of the buildings on the soft rocks underneath and the massive water absorption of the thick (one meter) rubble stone walls with lime mortar. The walls absorb the water in the wet months, releasing the humidity when they dry in the warmer months of the year. The very same lime-based mortar that reduced earthquake damage due to its flexibility is the cause for this extreme humidity. It is a fallacy to think that any restoration or new construction will improve this situation while preserving the historic structure. This aspect in itself will greatly minimize the ability to create a village that is open all-year with associated revenues.

Fase IV

This section describes improvements and restoration of the Castello area and even mentions the “aromatic essences” of botanical species in its garden. Given the multiple years before the previous phases may be completed the chance that this fourth phase will ever start is zero. The development document fails to mention the most basic requirements for the restoration of this area: necessity of an access road on the South side of town. For sure the pedestrian areas in town, which supposedly have all been restored and improved by the time that phase IV starts, will not be able to bear the traffic required for this restoration. Unless reconstruction is planned by means of manual labor or use of helicopters, an access road to restore the castle will have to be created via a new construction, with expense of multiple millions, surely more than the stated 5 million for a new parking area.

One of the other suggestions in this phase is the construction of a “ruin garden”. An interesting statement, because this “giardino tra i ruderi” was already created by the inhabitants many years ago.

"Gardens among the ruins" (area Rocche)

Fase V

Besides restoration of a fountain, this phase consists of the definition of a tourist strategy. The naivety of the development cannot be greater than by this statement. Apparently the strategy for improving tourism will only be determined after several tens of millions of (European) community funds have been spent in a period of over ten years. A ridiculous and unprofessional approach.

By this planned approach the authors of this development document prove their incompetence in the business area. Although the document does contain some good analysis of the historic status of the town (obtained through literature studies) it completely fails on the planned phased approach and clearly lacks any knowledge of the investments and time to complete the planned activities.

Chapter VI.4: Aspects of the surroundings

This section mentions but does not go into any detail on aspects that are critical to tourism: access roads, bus connections, footpaths. It naively suggests studying the option of landscaped, naturalistic, tourist and cultural itineraries leading to the Borgo di Bussana. It forgets to mention that these footpaths also make the tourists aware of the deserted immense and ugly flower auction buildings, the waste management plants, and the state prison. It mentions the possible adding of a parking area near the entrance of town. This is only feasible by eliminating the beautiful field in front of town, the location where the original inhabitants lived for years in barracks after the earthquake, in itself a sacred place. This campagnietta is the location of the antico cimitero, playground for the children and meeting place for the adults. Turning such area into a parking area would desecrate the Borgo di Bussana beyond any repair.

"Perhaps something may happen [...] although, at the moment, nobody seems to do anything." Sanremonews, Oct. 2017

Chapter VI.5: Estimate of costs

Basic and essential costs to prepare the area for restoration and stabilize erosion as well as many other items mentioned above have not been included on the estimate. A more realistic estimate of the costs will be in the range of 60 to 80 million euro. The specified phases are reversed from what any logical business approach would suggest and give no outlook to any income from tourism.

Looking at present tourism these costs will never be recuperated from additional income to the state and neither to any concession holders, thereby making this development a useless exercise.

Another catastrophic omission in this section is the maintenance expense. All reconstruction efforts need to be maintained and a budget in the range of 20% of annual expenses needs to be reserved. Based on the (highly insufficient) budget of 43 million euros, this means an annual extra cost of 8 million: 80 million of additional budget over a 10-year period. It is hard to comprehend how this amount can be recovered from the 0.5 million of annual tourist income. It would not even be covered if tourism grows tenfold.

Chapter VI.6: Estimated timeframe for the phases

Looking at the incorrect approach to the phases, the omission of the efforts required to prepare for construction, the duration of the ongoing legal procedures and the new procedures that will start in response to the erratic penalties issued by the Demanio, the suggestion in this section that the first three phases may be for a large part be completed in the coming six years is completely unrealistic. There are no precedents of a similar nature in Liguria or Italy that have been successful even within a ten year timeframe. Nearby destroyed towns such as Bajardo have been under reconstruction for more than 30 years and some parts are still inaccessible for tourists.

The suggestion that the definition of a strategy for the promotion of tourism may only start in 2022 is ridiculous.

Chapter VI.7: Potential funding options

On the top of this “dreamed” list is funding by the European community. Already the suggestion that this community would even consider to reserve any finances for a plan so incomplete is extremely naïve.

Before requesting any funding for restoration activities, either from government or European sources, a detailed market analysis of the attractiveness to tourism needs to be done. It needs to include the ability to grow tourism. The project plan and funding request will compete in budget with many other European projects as well as other projects in Liguria. Based on the access limitations of tourism and the unlikelihood to increase it, the program will fail to raise the necessary funds.

Looking at nearby large projects in the past 30 years we see a line of large-scale failures, both on budget and on implementation: from the megalomaniac construction of flower auction buildings that have been empty for over twenty years, an Aurelia-bis project in nearby Valle Armea that was delayed and useless because of “interventions” by local authorities for ten years, and the inability to complete even minor parts of the, in itself successful, pista ciclabile project such as near the old railway station of Arma di Taggia.

In the past I have advised the High Commissioner of the Finance Department of the European Union on budgets for large scale investments in infrastructure. Based on this experience I expect the chances of success for this project are zero. I am sure that it also will be insufficient to gain any funding from the Italian government. Even if some budget may become available, based on a complete rewrite of the development document focused on key aspects such as realistic tourism growth and a proper phased approach, it will become only available in the form of a series of increments each requiring the successful completion of the underlying phase within the allocated time and budget, and requiring a positive return on investment. There are many hundreds of other Italian and European projects that offer a better value than the plan sketched in the PdV.

Chapter VI.8: Tourist promotion strategies

A strategy to increase tourism, thereby establishing a firm basis for the recovery of the expected tens of millions euro investment in the Borgo di Bussana, is completely absent in the development program.

Recommendations are unrealistic and unprofessional and are in no way a foundation for a major financial investment.

If a basic analysis of current tourism would have been done, the limitations of this program would be obvious. As stated in the comments above: tourism streams to Bussana are currently insufficient to support even a basic income at social welfare level for the galleries in town and, without major investments in access roads and buildings, this will not improve.

The program sketches a scenario that resembles recognized artist towns such as Saint-Paul de Vence (France), without mentioning the many difficulties and restrictions that are present in Bussana Vecchia. This dead-end hilltop town with its destroyed buildings and humid galleries is no match for the French artist town that has several good quality roads passing through town and was built with far more modern construction techniques than the rubble stone buildings in Bussana Vecchia.

Saint-Paul de Vence, good for 2.5 million visitors per year, offers its visitors an exceptional panoramic view, rather than the view from Bussana Vecchia of the state prison, empty megalomaniac auction buildings and hundreds of unused greenhouses. Popularity of Saint-Paul de Vence was further greatly stimulated by the presence of artists like Chagall and Picasso. None of this is the case in Bussana Vecchia.

Bussana Vecchia and Saint-Paul de Vence (right side)

This chapter does not do more than to list a series of possible options. It fails to recognize that it will take years to create a working strategy and more then ten years to effectively increase tourism. In the mean time, none of the (private) investors/concession holders in the infrastructure will see any positive return for ten or more years, if any.

This chapter throws in the “modern” social media, apps and 3D viewing as a potential improvement for tourism, without mentioning that all of these items have already been created by the present inhabitants in cooperation with companies like Google.

Chapter VI.9: Management aspects

The development program specifies that management of the plans, strategy, and implementation of the phases will be managed by the municipality of Sanremo. I am pleased to read that this chapter suggests including the only group of people that are experts on the topic of Bussana Vecchia: its residents.

Both the state and municipality abandoned the Borgo di Bussana after the earthquake and “intervened” by destroying many buildings in the 1940’s and 50’s with explosives. It has not done any effort to improve the town in 130 years.

The attractiveness of Bussana Vecchia for tourism is for 100% based on the personal investment, the hard labor and sweat of its inhabitants. They removed the rubble, they built the utility infrastructure, restored buildings so that they can be used for galleries, shops and residential living, they have maintained the infrastructure for over 50 years, and they have done the marketing, the promotion, the websites, and the apps. This unique spontaneous architecture effort, creating new living spaces in the areas deliberately destructed by the municipality/state with explosives, has made Bussana Vecchia world-famous. It is time to recognize this success and their knowledge and cooperate towards a higher common goal.